INTRODUCTION

A few months ago, my youngest biological brother, Eric, sent off some money and a DNA swab to Ancestry.com, hoping to fill out a few more of the branches on our shadowy family tree. Most of our genealogical story is spread through my mother’s father’s side of the family, The Schleyers, who emigrated from somewhere in (the confederated states of) Germany and set up shop in Brooklyn, New York in the late nineteenth-century. My mother’s mother was adopted, as was my biological father. Neither know their “stock” — to borrow the proto-racial language of the 18th century — and so their histories go as far back as 20th-century Queens. Thus the family tree we’d known for all of our lives was, let’s say, trunk-ated.

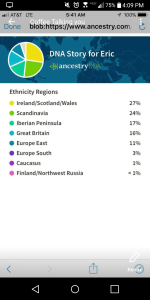

I too was eager to see what Eric’s search turned up, and yet when the results came in I was underwhelmed, or, disappointed maybe. As the screen-captured chart above states, I’m a quarter Irish, some mixture of Scandinavian, British, and “Iberian,” with a smaller amount of vaguely-located “European” genes (and with further clicks, the map reveals that “Germanic” ancestry actually cuts across much of these areas, too). Alright, so what kinds of cuisine do I ironically enjoy? Which ethnic stereotypes should I cosplay? What soccer club do I support during the World Cup? Most importantly, what am I? The Robbins’ DNA story seemed a rather discontinuous narrative, and it left any ethnic identity even more uncertain than the family lore of our childhood. But isn’t this just the truth of ethnic identity writ large? It’s desire to root human bodies to the national myths of landed property was always already fictional.

Notice I’ve said nothing yet about “race,” which is, after all, one of the central themes of this course. Another way to render the ethnological results above is to say simply this: I am white. (One could say, no, you’re an American of European descent, but – and here’s a main contention of this class – that’s only to say the same thing.) Whiteness, or, in this case, “being white” – and that’s not the same thing – is a fiction. The great African American essayist James Baldwin famously called “being white” a “lie,” going even further to claim that “No one was white before he/she came to America.” Race is a fiction, a lie, the ideological cover of European colonialism and the system of human chattel slavery it produced and sustained in the course of its historical life.

I am making the case here, – as this course, “Whiteness and the Working Class,” turns upon this argument – that race and racism are inseparable from and malleable according to the economic conditions of any given historical moment. This is to say, we can’t really talk about “whiteness” as a lived, historical, or cultural phenomenon without thinking about social class. After all, the Schleyers weren’t of the well-to-do German aristocratic stock. They were peasants and workers, but the “price of the ticket” – as Baldwin so shrewdly identified it – of becoming white in America was to exchange national identity, rootedness in local traditions, for a new kind of racial privilege. That’s the story of European immigration to the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries, this is the true “DNA” story of the Robbins family: we became white.

So this course, of “whiteness” and the “working class,” will sketch the sometimes confusing contours of racialized experience in the United States (and, potentially, beyond its borders). After all, a part of being white in America, for me, a child of the 80s-90s, was the benefit of never really considering what it meant to be white. Whiteness was an absent privilege; my experiences were rendered “normal.” As for social class, my father and mother, construction workers both, managed to move us into the suburbs of upstate New York during the economic boom times of the Clinton era. Our manicured back yard, our state-of-the-art gaming systems, our above-ground pool, our barbecues, our little league seasons – these were the markers of the American middle class. What it meant to be “working class” had no resonance until my father was periodically laid off and then “let go” following the financial collapse of 2008. As his work grew more precarious, I recognized that class had less to with income and consumer products than with power, namely, the power to have some stability, some say over one’s life and work.

And so you know, we live in interesting times. Against a background of revived civil rights movements for racial and economic justice in America – and its ever-entrenching reactions: a newly intensifying and politicized white supremacy along with ballooning economic inequality – the country now talks about “whiteness” and the “working class” as if those categories, those demographics, were always so obvious. Unfortunately, our popular discourse tends to confound these realities, maybe willfully so, so I see this course as something of an intervention for the sake of clarity and awareness (and, believe it or not, ethical conviction.)

The Specter of Trump

Let’s be very clear. This is not a course about Donald Trump or about Republicans or Democrats or how you or I or anyone in this class might have personally voted in the previous Presidential election. At the same time, the demographic reawakening of the “white working class” sparked by Trump’s campaign has – in the country’s popular imagination, at least – cracked open the fault lines along race and class supposedly sutured by the election of Barack Obama. We shouldn’t accept this narrative at face value, but rather explore its motivations and its success in the nation’s cultural imagination.

I’ll admit, I have struggled with exactly when and how to approach the most recent election in the course of our semester. It is, I think, an inescapable fact that notions and experiences of race and class (and gender and ablebodiedness, etc.) determined the latest round of electoral politics, and continue to dominate the cultural politics of the country more generally. So while “Whiteness and the Working Class” isn’t a “political” course, in the strict definition of breaking down electoral results or studying policy decisions, it exists within and, quite frankly, as a result of our political atmosphere. We need to be prepared to confront these realities in our class discussions while being un-apologetically rigorous and grounded in our critiques and resolutely kind and open in our exchanges.

Speaking Openly about Race and Racism is the Only Way Forward

We all know the now well-worn memes of trying to avoid uncomfortable political discussion with friends and family during the holidays. But as a result of the omnipresent divisiveness of contemporary political life, that trope has intensified to such an extent that these racial and class politics are always imminent, encroaching into every (formerly pristine) corner of media and entertainment.

During the holiday break, I visited with family and friends back home, in a majority-white rural locale in upstate New York. My town, Dover Plains, – located roughly 90 minutes north of Manhattan, an uneven blend of suburban commuter community and “local” farmlands and precarious ma and pop stores – provided a unique window into our political moment. In my conversations with Trump supporters (and that’s just about everyone I know excepting my immediate family), I recognized two things. First, it was unmistakable that a kind of aggrieved whiteness was being given a brazen political voice. All the seemingly minor, offhand comments that peppered my adolescence — friends’ and family complaints about “Mexicans” taking jobs, about the “reverse racism” of affirmative action, about the danger of “inner cities” and the disrespect of “those young people” sporting baggy pants, about the castrating effects of political correctness gone wild — found a vocal champion in Donald Trump.

But I also discovered that this very interpretation of mine –i.e., what I was literally seeing and hearing from — had little resemblance with their own understandings. For my friends, – most of them working in low-paid service sector jobs, many struggling with debt and addiction – Obama’s election had proved the relative equality of race relations; instead, it was Black Lives Matter, kneeling football players, immigrants here “illegally,” and a host of other “social justice warriors” who had whipped up racial resentment. Because discussions of race had been, for them, relatively muted, this was proof enough that racism was no longer a potent force in American life — but for the few bad apples, like those marching in Charlottesville, who continued to insist on the supremacy of whites. If anything, to bring up the imagined slights of Black- and Hispanic- and Asian- and Arab- Americans had in itself reignited racial turmoil, since,– with all an equal footing — it was white people, shouldering the guilt of an invisible “privilege,” who were actually discriminated against for their race. This sort of “colorblind racism,” “racism without racists,” as Eduardo Bonilla Silva calls it, is another of the core issues we’ll make visible this semester.

What This Class Is and What it Isn’t

I want to close my invitation to all of you with a proposal: let’s talk about race and class honestly, openly, critically, and yes, personally. As an instructor, I’ve erred in the past by assuring students that any discussion of racism was only structural, oppressive and embodied in systems, in language, in culture, and in ways we can’t always be aware of.

On some level, this is true. But that framing is also very misguided. Politics, culture, history – the provinces of this class – can’t help but be personal. To be rigorous doesn’t mean we have to be abstract and impersonal. In fact, we learn more and better when dealing with ideas as concrete manifestations.

But, another warning: though we, as individuals, will interrogate how we make up a much larger network of relationships are that affected by and effect race, racism, class, exploitation, this doesn’t mean we need to collapse into a pity party. This class is about recognition, not resignation; it’s about empathy, not commiseration; it’s about ethical testimony, rather than moralistic damnation.

The big idea here is that race is not real. It’s a fiction of power relationships. It’s lived and has real material consequences, but there’s no biological, historical, or cultural or ontological realness to race.

What else to keep in mind? This is not a class that will delve in stereotypes, though it is concerned with representation. It’s not –as an increasing number of right-wing media outlets will claims–a class about “hating” white people, of which — and this might surprise you — I am.

Furthermore, it’s not a class of “radical” leftist propaganda. Our agenda is exploration. The only radical presupposition in this course is that students can and will think for themselves.